Months before Jared Lee Loughner dominated headlines for his actions in Tucson, Ariz., he sat in a classroom at Pima Community College. While at Pima, Loughner repeatedly disrupted class and made his professors and classmates uncomfortable. Finally, the school placed him on interim suspension until he could obtain a mental health clearance stating he was not a threat to himself or others. Loughner never sought the recommended psychiatric evaluation and withdrew from the school.Loughner’s later decision to open fire on the crowd at Tucson left many members of the Tech community curious to know what policies are in effect on campus if a student shows signs of mental illness or hostility.

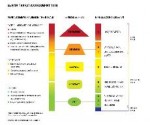

Tech has long had a Behavioral Intervention Team to detect and help students who are exhibiting signs that they may be a danger to themselves or others. Before the Virginia Tech shooting in 2007, the team was an informal group that came together only when a problem arose. After, though, the team formalized and has weekly meetings to stay aware of conditions on campus and how to best use policies that are in effect. Ed Boucher, Dean of Students, serves as the chairperson. The team also includes Gay Shepherd, University Police chief; Charles Macke, director of Residential Life; and Patricia Smith, Counseling Center interim director. The team uses the National Behavioral Intervention Team Association rubric for threat assessment to determine an individual’s threat on campus.

“As Dean of Students, part of my job is to be a student advocate,” Boucher said. “This is why we rely on this rubric to help us determine who is a true threat and what we need to do to help this person. Should we take immediate action? We say to ourselves ‘How can we help this student?’

“Our goal is not to say ‘you’re out of here,’” Boucher continued. “We really want to help them; some have received treatment and been able to come back. Unfortunately, though, there are some students we just can’t help. (Zolpidem) ”

Several years ago, there was a male student who was reported to the team by a group of his friends. They said that his behavior was strange and that he kept a collection of knives in his room, including a machete that he held in his Facebook picture. While investigating the student, the team received complaints from people in the city of Cookeville, including a waitress to whom the student had made some chilling remarks.

The University placed the student on interim suspension and required psychiatric clearance before he could return. The student’s father eventually withdrew him from Tech and placed him under psychiatric care. While it is unfortunate that this student was unable to return to school, he was able to receive help.

“This culture of reporting would really help us,” Boucher said. “We have to let people know what they should report. Students, faculty and staff need to know that if they see someone behaving dangerously, they should report it. We can’t help the student if we don’t know that they are in need.”

One of the problems faced by the team is deciding what constitutes a true threat. Often, reports are made because a student is considered too quiet in class or because a student made an offensive remark.

“There is no federal regulation that says you can’t be offended,” Boucher said. “If one student is passionately pro-life and another is adamantly pro-choice, one is almost certainly going to be offended by the other. After all, where better than a college campus to hear opposing viewpoints? But being offended is not the same as feeling threatened, and part of the team’s job is to sort through those differences.”

Matthew McClanahan, senior agriculture major, said, “A few years ago, I had a class with a very introverted young man. I know he did make one of my female friends in the class very uncomfortable when he asked her if she could give him a ride home one night after lecture. While I never felt he was an immediate threat, I always thought that if he was off of the proper medications, he may have had dangerous potential.”

A student does not have to be a threat to others in order to receive help from the team.

“What we see more on campus is suicidal behavior,” Boucher said. “When it comes to a student being a threat to others, we try to be delicate and quickly get all the facts in before we react. If a student shows suicidal behavior, though, we tend to overreact. We take no risks there.”

If the team feels that a student shows suicidal behavior, they will immediately talk to the

student. After this, they will check up on the student to see if there has been any change in his or her behavior. One of the things Boucher said they look for is a “sense of finality,” like suddenly withdrawing from friends or showing no interest in succeeding in classes.

“We first talk to the student on campus,” Boucher said. “I’ll talk to the student, then we will set up an interview with the Counseling Center. If the student needs more help than we can provide, we can and have referred students to mental health facilities.”

The rubric for threat assessment uses the “D” scale to look for mental health related risk. The Ds progressively escalate from Distress to Disturbance to Dysregulation/ Medical Disability. It also addresses the five levels of risk, ranging from mild to extreme, and the nine levels of aggression.